The eLand of the Dead (Ephemera 05)

In which I explore the 'mix between a genuinely held conspiracy theory and a collaborative creepypasta' that explains why the internet sucks now

It started about a year ago when I was attending a talk by a supporter of generative artificial intelligence - aka Gen AI - who explained that, when he goes to the gym, he has a Gen AI tool create music based on criteria he sets. The example he used was ‘fast paced guitar pop punk in the style of blink-182’; the resulting track sounded exactly like that. I tentatively raised my hand and asked “so, why wouldn’t you just listen to blink-182 at the gym?”

He didn’t have an answer.

But it hit a boiling point this week as I was looking at mindlessly scrolling past yet another AI-generated fake action figure, a trend which has officially made it around to boomers on Facebook who are delighted with the weird little thing those youngsters are doing with the internet these days.

A little lower down, I found a cartoonist who had drawn by hand her own action figure, in the caption begging people to be aware of the risk Gen AI poses on creative industries of all kinds, including this very SubStack.

I don’t think there is anything or anyone real on the internet anymore.

Or to put it another way:

I don’t know what is real and what is fake.

What is this s***?!

I swear it didn’t used to be this way. When I was 13 or 14 years old, our family got our first computer, and within a year we were on the internet at the epic high speed of (checks notes) 28.8k via dial-up. The internet was bereft of videos, and mostly empty of images, so there was a lot more reading to do, and most sites and apps seemed focused on chat. Internet chatrooms were everywhere. I used to chat to people all over the world - and it felt safe and exciting and new.

Later, there was mIRC, which was the first sign at what the internet might become - a community of basic text chatrooms sorted by subject. Parts of mIRC were a bit like a forefather of 4Chan and Reddit, but there were moderated safe spaces there that were still based on chatting.

And before Facebook and before MySpace, there were chat apps like MSN Messenger and ICQ, where you could add friends you’d met online - and real life friends - and chat. I fell into a community of people who were primarily interested in sharing music and sharing their life experience wherever they were. I used the nickname Xizang. I have no idea what it means; I saw it on a sticker on a mountain bike a friend of a friend was riding.

It felt like I was living in the old promise of the internet.

Then it kept getting more and more … toxic is the best word I can think of to describe it. The last 20 years have seen the internet turn from an idyllic ocean of possibility to an expanse of human waste that shouldn’t be in there (so like the real ocean). And its getting worse: whenever I go on the internet, I feel overwhelmed by the fakeness of it all.

Nowadays, it feels like so much content on the internet is generated by AI - or to clarify, by people using AI to create mass amounts of content on the internet as a way to make money through click revenue. Internet searches are full of AI slop, a ‘term of art, akin to spam, for low-rent, scammy garbage generated by artificial intelligence and increasingly prevalent across the internet’, according to writer Max Read. Almost everything reads and feels like meaningless trash.

And as much as I love Wikipedia, routinely the top result, its not exactly a perfect source of truth; sure, its cleaned itself up and is well cited, but a 2011 study found that only around 10% of editors were female or gender diverse. Most were mid-20s males who, as we all know, are well known for their knowledge.

(It was also recently revealed that AI was used to translate almost the entirety of Wikipedia into Cebuano; now Cebuano Wikipedia is the second largest Wiki, even though Cebuano isn’t in the Top 40 most spoken languages worldwide. While this seems like it might be a net good for Cebuano speakers, the use of AI is what makes the story feel problematic.)

Its not just internet searches. Social media is full of trash as well. My average visit to Facebook involves me scrolling through my timeline past ads, past recommended pages and, very occasionally, past someone or something I actually follow. I did a very unscientific measure of this and found that, across a dozen visits, an average of 7 of the first 10 things I saw on Facebook were things I had not followed. Instagram is just as bad. TikTok too.

Reddit is going the way of those apps as well. I love Reddit. I get a lot of joy out of Reddit, as well as a lot of news, both local and global. Yet my home page is increasingly recommendations and ads, somewhere in the order of 5 out of the first 10 things I see usually.

Honestly, when I venture into /r/All, it feels like I just dropped into a swap meet for nonsense I dreamed up and made ChatGPT draw for me, or write for me, or invent for me. How many of those obviously fake ‘My (21f) boyfriend (64m) is an objectively bad person, should I leave him?’ posts do I need to see every day?!

It’s at the point that every time I see a weird grammatical decision or a spelling mistake, I assume its AI related. A strange word choice in a review of The Last Of Us’ second season. A couple of spelling mistakes in an article about physics.

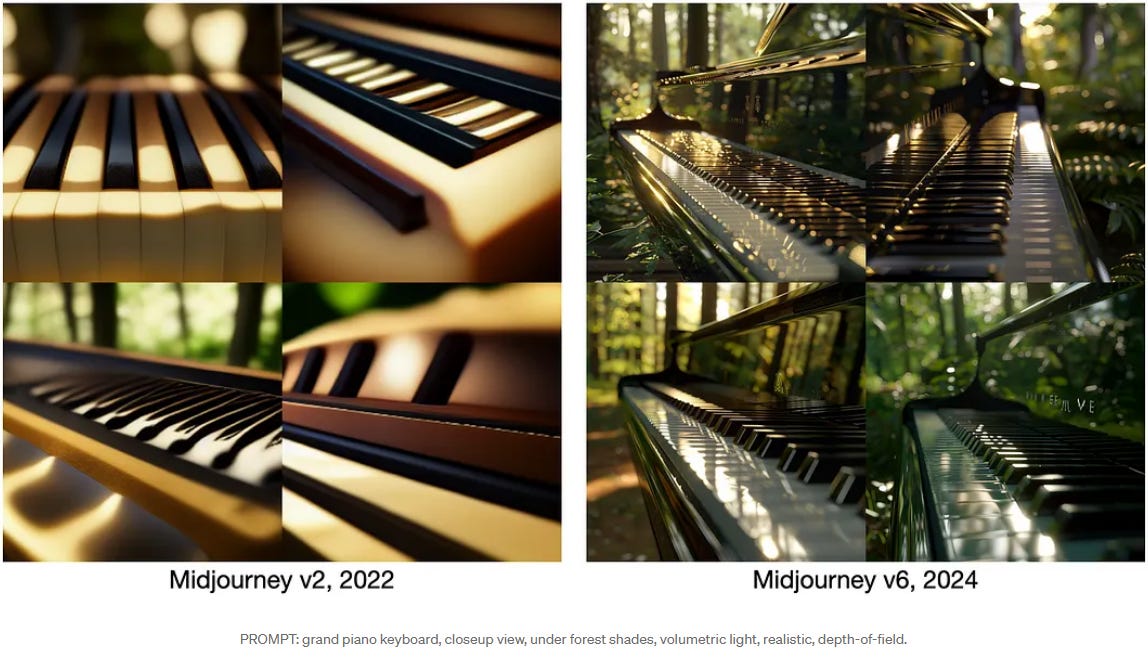

And then it stepped up this week: a handful of video posts with titles like Both video and audio is AI but it feels so real and Wtf, AI videos can have sound now? All from one model? and All these videos are ai generated audio included. I’m scared of the future - that last one might be a little scary for younger viewers. These videos are nearly indistinguishable from real life. And when you consider they are always improving - as gen-AI tools like Midjourney have done for the past few years - the task of sorting real and fake is only getting harder.

Online content is absolutely cooked.

L’internet est mort!

It turns out I’m not alone in feeling this way. In fact, there is already a full explanation for this: the Dead Internet Theory, ‘a mix between a genuinely held conspiracy theory and a collaborative creepypasta’ as AI philosopher Robert Mariani described it. It sounds crazy. But is it really?

As Max Read explains in a piece for New York magazine:

Studies generally suggest that, year after year, less than 60 percent of web traffic is human; some years, according to some researchers, a healthy majority of it is bot. For a period of time in 2013, the Times reported this year, a full half of YouTube traffic was “bots masquerading as people,” a portion so high that employees feared an inflection point after which YouTube’s systems for detecting fraudulent traffic would begin to regard bot traffic as real and human traffic as fake. They called this hypothetical event “the Inversion.”

He goes on to clarify that funny feeling you get reading or viewing content online, that sense I got finding those spelling mistakes or word choices:

Everything that once seemed definitively and unquestionably real now seems slightly fake; everything that once seemed slightly fake now has the power and presence of the real. The “fakeness” of the post-Inversion internet is less a calculable falsehood and more a particular quality of experience — the uncanny sense that what you encounter online is not “real” but is also undeniably not “fake,” and indeed may be both at once, or in succession, as you turn it over in your head.

Robert Mariani imagines a 2026 where all of this spirals out of control: online scams are perpetrated by bots, social media companies require payment as human verification leading to site isolation, sites like Reddit and 4chan are over-run by fake content, a handful of TikTok’s up and comers are revealed to be deepfakes made by the same person, the trial of a hacker is declared a mistrial after nobody can determine what was the hacker and what was a ChatGPT clone, a Wall Street exec is charged with widespread fraud …

In 2026, the sun sets on the era of the Internet that was synonymous with human interaction. Adrift and sedated in the dead Internet, people are more alone than at any other time in history, and the mental health implications are predicted to be catastrophic.

Okay, this feels a little alarmist. But …

Doesn’t it feel just a little bit believable?

Vive l’internet … ?

So, what does the future of the internet look like? And how do we keep it real?

It seems like most large platforms - the Metas and Alphabets of the world - are trying to limit the effect that generative AI has on their websites, investing in resources to find and remove fake content, purchased likes and such.

But they’re doing those things even as they contribute to the issue: Google uses AI to summarise search results, while Facebook provides an AI assistant to create posts for you - and more than that, they expect it will eventually function like an actual profile. “We expect these AIs to actually, over time, exist on our platforms, kind of in the same way that accounts do,” says Connor Hayes, VP of product for generative AI at Meta. “They’ll have bios and profile pictures and be able to generate and share content powered by AI on the platform.”

One of the biggest variables is the proliferation of large language model (LLM) AI platforms like Chat-GPT. Timothy Shoup from the Copenhagen Institute for Futures Studies predicts that, should one of these LLMs be let loose on the internet, as much as 99.9% of online content would be AI generated within just a few years. “The internet would be completely unrecognizable,” he notes.

What can we do as internet users?

There is no question that platforms like Chat-GPT are helpful. If you work in an office environment, think about how quickly the use of AI has become a normal part of your day. Just thinking about my own job, we have one AI assistant in our data analysis tool which helps with locating data and coding, another in Microsoft Office that helps with apps like Outlook and Excel, and Chat-GPT use is widespread as well, primarily for tasks like generating ideas.

We even use AI in our weekly Dungeons & Dragons sessions: it can turn bullet points into a full summary in any style, it can generate names for a ship we just acquired, and it can create images of the players and locations based on the DM’s descriptions. One player even uses NotebookLM, which turns his notes into an entirely AI-generated audio summary that is nearly indistinguishable from any other podcast you’d care to name.

In a work environment (and at D&D), the key has to be establishing strict rules around when and where AI can be used, providing training for responsible use, and stating when AI contributes to a piece of work.

Home is a bit trickier. If we learnt anything from the widespread sharing of misinformation that has taken place over the past decade - and the adoption of conspiracy-like beliefs by a demographically broad large percentage of the population as a result - its that a large amount of the population doesn’t question what they read online, especially if its shared by a trusted friend or relative.

Maybe the horse has already bolted on that front.

Regardless, as a parent, I can teach my kids how to think critically, how to question what they read and see online, how to look for hallmarks of AI content.

As a friend, I can do pretty much the same: calmly and respectfully share evidence that something isn’t real, and refute demonstrably untrue beliefs. And when I find content that I know to be trustworthy, share it more widely.

Look, I love the internet. I didn’t grow up with it - it arrived on my doorstep one day in my teens, and in many ways I’ve grown alongside it. I love finding new and useful sites. I love learning about topics I know nothing about, and going on deep-dives into obscure subject matter. I even love using AI for certain tasks; an AI tool at work has basically taught me how to code in SQL over the past year.

I don’t have satisfying answers for any of this. But what I do know is that ‘dead internet theory’ - true or not - has become something that I think about on the regular; I catch myself questioning the veracity of content online, wondering if that spelling mistake or sentence structure is a sign of AI. My instinct is to fight back. I hope yours is too. Because I don’t want the internet to die.

Vive l’internet!

Ephemera is my ongoing series in which I look back at moments in pop culture that live rent free in my brain. Previously editions:

01: A 9/11 literary trilogy (September 11 Attacks)

02: This is how you lose the Prime war (Prime Hydration)

03: Funny 'ha ha' or funny 'la la'? (Bo Burnham’s That Funny Feeling)

04: No spoons for Uri Geller (mentalist Uri Geller)

Also, I can promise you I am a real person. No, really. A bit of a rambly and semi-paranoid one today, but its something that has been on my mind, and I felt compelled to write about it. Hopefully you got something out of it too.

Fun fact: I had my six year old help me get Chat-GPT/Dall-E to create the main cover image for this post, eventually using the prompt “Please make me an image of a giant red-headed/shoulder length hair six year girl fighting a kaiju that is a combination of an armadillo and a gecko in the centre of Auckland City CBD, with lightning shooting out of her fingers, and make it as realistic looking as possible. And make them as tall as a skyscraper." Yes, I say please when I use AI; I’m not looking to fuck around and find out with Roko’s Basilisk.

I’ll be back tomorrow with Singles In Your Area.

Mā te wā,

Chris xo

I think about this all the time as well :|

Yes! Agreed.

I'm very keen to leave Facebook (already only use it for one published page and a dozen or so groups) and Instagram as I find them more and more frustratingly full of ads and content that's just mind-numbing.